A humanitarian issue of critical concern

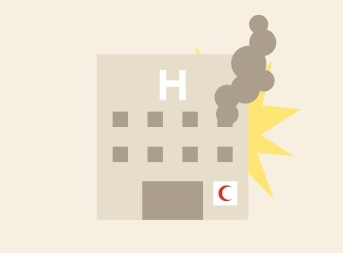

It is when fighting breaks out that health-care services are most needed, but it is also then that they are most vulnerable to attack. Doctors and nurses, ambulance drivers and paramedics, hospitals and health centres and even the wounded and the sick have all come under attack.

This violence can disrupt the health-care system when people need it the most. Combatants and civilians die only because they are prevented from receiving medical attention in time. Entire communities are cut off from vital services, such as maternity care, child care and vaccinations. Sometimes the disruption can be so severe that the entire system collapses.

Violence against health-care workers, facilities and vehicles, therefore, is a humanitarian issue with widespread and long-term effects. We need to address it together.

10 Years of Health Care in Danger in the Movement

While the protection of health care goes back to the very origins of the International Red Cross and Crescent Movement, special attention has been devoted the protection of health care over the past decade. The genesis of the Health Care in Danger Project and Initiative was brought about through the adoption of Movement Resolution 5 of the 31st International Conference in 2011 and Resolution 4 of the 32nd International Conference in 2015.

Since 2011, the Movement has significantly contributed to the protection of its own health staff and volunteers and to reducing violence and its impact on health care more broadly. By profiling the experiences of colleagues from the Colombian Red Cross, Somalia Red Crescent Society and Nigerian Red Cross Society, the meeting seeks to cast light on the experiences and contributions within the Movement on the protection of health care with this decade long trajectory in mind.

HEALTH CARE SHOULD NEVER BE IN DANGER

In 2016, the United Nations Security Council adopted a resolution calling for an end to impunity on attacks on health-care workers and facilities. Since this time, the International Committee of the Red Cross counted 3,780 attacks between 2016 and 2020, in 33 countries affected by violence or conflict. This makes an annual average of 756 incidents – of attacks, threats, gunshots, fires, kidnappings, shellings, killings and directed violence – that target health-care workers around the world.

This film looks at the practical solutions to protect health-care workers and facilities from around the world and shows that there are direct actions we can follow, implement and share to meaningfully mitigate and prevent violence that targets health workers

The many forms of violence

Understanding violence against health care is crucial. It involves looking at the different forms that this can take, and who the targets and who the perpetrators are. Only then can effective measures be put in place to ensure that wounded and sick people have access to health care and that the facilities and personnel to treat them are available, adequately supplied with medicines and equipment and are safe.

Definitions:

Violence against health care personnel. What is it?

Violence against health-care personnel includes killing, injuring, kidnapping, harassing, threatening, intimidating and robbing health-care personnel; and arresting anyone for performing their medical duties, including the impediment and arrest of forensic professionals while performing their forensic medical duties.

Violence against medical vehicles. What is it?

Violence against medical vehicles includes attacks upon, theft of and interference with medical vehicles.

Violence against the wounded and the sick. What is it?

Violence against patients includes killing, injuring, harassing and intimidating patients or those trying to access health care; blocking or interfering with timely access to care; the denial of, or deliberate failure to provide, assistance; discrimination in access to, and quality of care; and interruption of medical care.

Violence against health care facilities. What is it?

Violence against health-care facilities includes bombing, shelling, looting, encircling, forcibly entering and shooting at or into health-care facilities, and any other forcible interference with the running of such facilities (such as by depriving them of electricity and water).

Health-care personnel include doctors, nurses, paramedic staff, first-aiders, forensic medical staff and support staff assigned to medical functions, the administrative staff of healthcare facilities, and personnel.

Medical vehicles include ambulances, medical ships and aircraft, whether military or civilian; and any other vehicles transporting medical supplies or equipment.

The wounded and the sick include all persons, whether military or civilian, who are in need of medical assistance and who refrain from any act of hostility. This includes pregnant women, newborn babies and the infirm

Health-care facilities include hospitals, laboratories, clinics, first-aid posts, blood transfusion centres, forensic medical facilities, and the medical and pharmaceutical stores of these facilities.